|

A libretto, a fragment of a libretto, a study of a mother goddess with a missing child. Demeter after the abduction of Persephone; a spoken word unraveling over a texture of aggressive beats and noise. I wanted to leave it here – unfinished and flawed, but raw and special right after the making..

I have been lying Asserting / indoctrinating my daughter, simulating idealism…… ignorance that she/one/they/I/have/has agency. that within these systems within these confines she can control/change/impact/better/define/create her-self. That she/her beautiful will won’t be broken. Shhhhh, baby. quiet. It took me forever (a lifetime) eternity (a moment) to learn that my body is not mine. my being/my-self/my time is not mine. identity is not of my making. it is draped over me and assigned. gifted by authority. it would/will be used, a weapon against me. separate from me. I climb in and out of it [repress/restrain/regulate/subjugate/subdue] discipline, authority: Pried loose in violence, eroded [grind, shiver, rasp, erode] ignus fatuus: control through desire manipulation the inevitable need/want/loss but I thought I could erase the transgression of subjecting her to this place, these systems, this rotting sphere and its flawed architectures. as if the crippling social norms and constant abuses of power could be undone through love and gentle teachings: reach out gentle fingers to trace and caress when we touch it, the landscape shudders and bends. I/we/you become real in the touching, the shaping, the sensual For a moment: speak. Arch toward something and finger it loose. Pry it up and open with small hard teeth. [t’s are hard for her right now] but you are not me and I am not her and they are not…listening. they cleave her from me patriarchal hubris appeasing lonely want a bauble of light between shadows her cancerous absence, a hollowing metastasizing the fields blight and drought take root without her green witch hands to prune them back I become goddess weeping ash Untethered in my grief, tearing at my own skin to be free of it, splintering The shards of this self, piercing deep into earth I am the goddess undone Seeping bruised and wasted into the beckoning void I/she/her/we/us/they become delusions and wraiths you, your body, your hands (conspicuous/persuasive) me, my cry, my possession (ephemeral, invasive, contrived) differentiated. (please) let us make [or believe] - you allow me this deception. that I am not being [now] that I am not mute [here] that these attempts at begging the world be different than it is are communicative, not feeble. But further and further I am/I become, in this impossible In this, I am broken – prismatic. Voice cleaved from body, body reft from thought, thought stripped of the illusion of agency, of control. possession. and in my heart’s dying, so stills the world

0 Comments

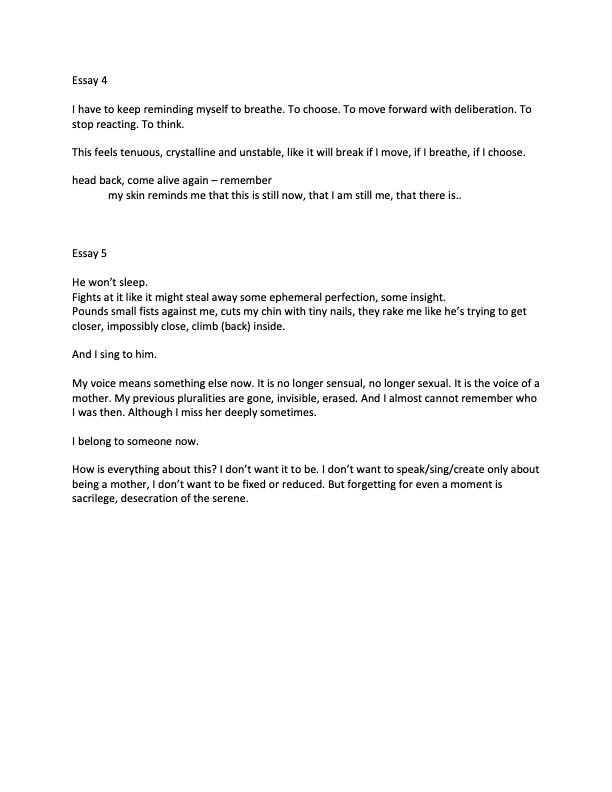

This is an excerpt from my recent narrative environment score, she/storm. Narrative environment scores represent a new aspect of my creative research, but one with which I’m quickly falling in love. I wanted to work through a few of these ideas here, fix them (rather informally) and mark this moment in exploration, especially as I finish this piece for The Nodes Project and begin working on earnest on another work in the series for the fiercely talented Shanna Pranaitis.

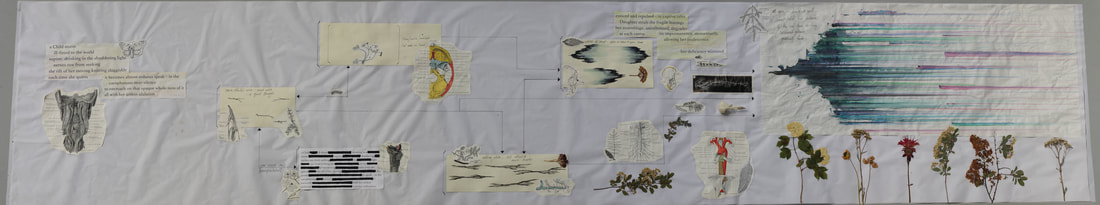

This new direction of inquiry is born of several desires: first, to situate the performing body of the musician and the effort of making sound. Second, to establish a shared aural-visual world for listener and performer that evolves temporally. Third, as a more explicit means of engaging with concepts of narrative theory, a primary organizing principle in my work over the last several years. And the last might still be too vague to discuss, as I am just beginning this research, but I want to try to articulate it: as a means of amplifying the plural causal associations of sounding objects. While I find the world of ‘noise’ [loosely defined as extended techniques and found sound] to be breathtaking, rich, evocative, intoxicating, and engaging…(too much? not enough?), I realize the abstractness of these sounds, as they exist largely outside of the established semantics of western art music. It isn’t that we don’t have wonderful and effective means of thinking of the structures for tension and release, or the hierarchies of sound: I love the elegant sound/noise axis that Saariaho describes, and I find Lachenmann’s ideas of energy and assembling give amazing insights into potential taxonomies. But these concepts in combination with the non-linear narrative associations triggered by the video contexts seem to provide an incredible depth of meaning and life to the previously abstract (reduced) ‘noise.’ Not in service to a visual foregrounded element (as sight seems to take precedence for most of us), but as a treasure-trove of potential meanings that can situate these ephemera in time and musical memory. Perhaps…. she/storm‘s physical score was created on two 2’x11’ vellum sheets – it is a structured improvisation score, combining found objects, graphic notation, and text direction. The performers are given static (printed) copies of the sheets and detailed performance notes in addition to the video score. The video exists as triggered media which is controlled by one of the on-stage performers: four distinct files, each encompassing a formal section of the piece, triggered when the ensemble is ready to move to the next section. We will start in Oshtemo Park (7275 W Main St. Kazoo, MI). Please remember to wear your masks at all times – consider insect repellent and wear clothing appropriate for hiking in semi-muddy conditions.

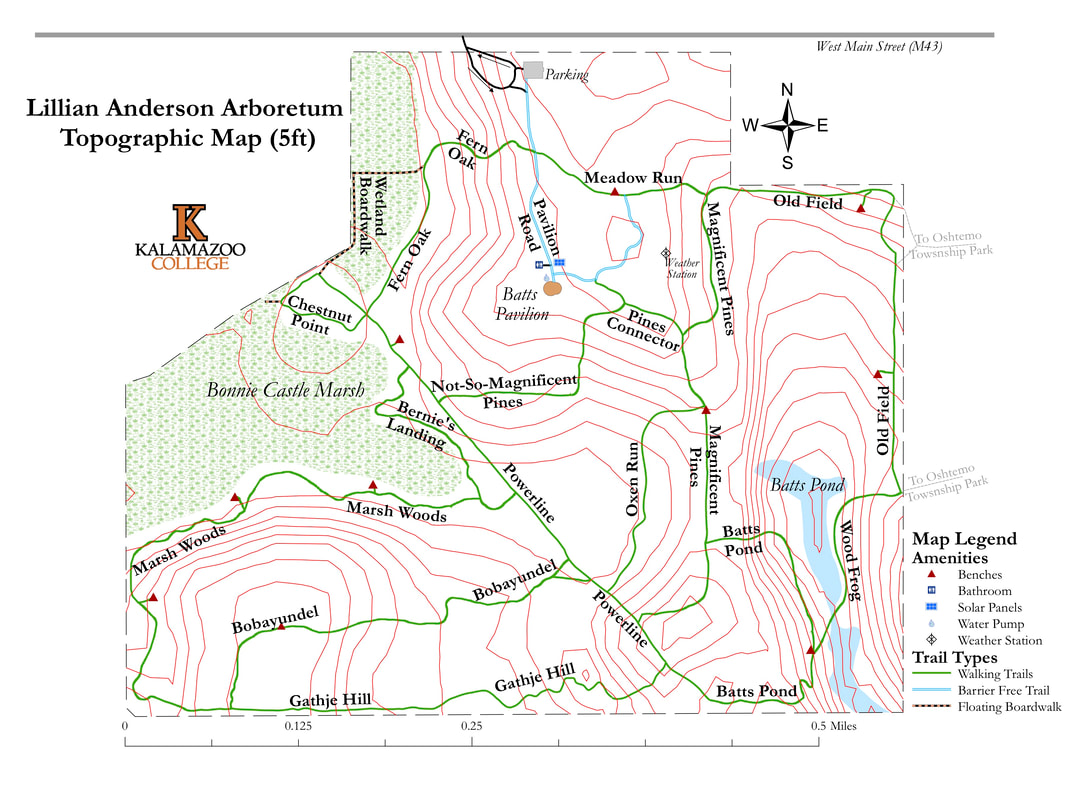

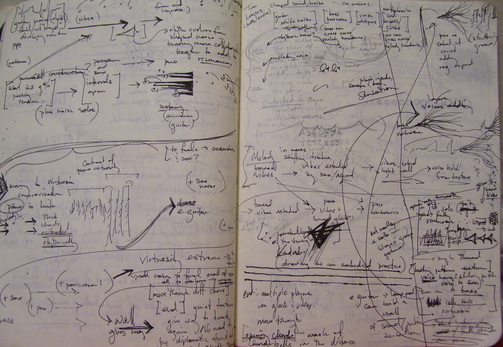

~Take a moment to be still, do not move / do not seek. Let yourself listen (perhaps taking a moment with eyes closed, to recalibrate your senses). Consider the sounds that come to you, give each its own space – gently shift between the immediacy of coded listening and the aesthetic qualities of the sounding objects. Slowly allow the sounds to intrude on one another, to let the soundscape of the park amass in your awareness. ~Begin moving at a pace that fits your listening practice. Travel east on the trails toward the arboretum, away from the playground and past the golfers at their games. Attend the change of perceived tempi as your body moves, and do not hide from the sound of your breath or steps, but let them fit within those external rhythms. ~Focus not only on what is present, but how the sounds change as they grow proximal or distant. In the Arboretum, head south along Old Field and Wood Frog. Please stop if a sound comes to you that is better heard when still. Move with empathy for the creatures of Batts Pond – tread lightly, making space for their delicate songs. The bridge shows the wear of time, but its cobbled aspects make for plural soundings. ~Continue south as the trail loops around, cross the clearing into Gathje Hill– move more quickly here, find a rhythm to reset your senses– likely your sight will again be foregrounded as you negotiate the terrain. Try stopping at times and quickly closing your eyes along the Marsh Woods loop – attend to the shift in your hearing and smell with the cessation of motion and the abrupt interruption of sight. Try slowing as you near the end of the Marsh Woods loop, perhaps taking a moment to sit at the edge of the water. Let your eyes grant substance to the gentle echos at the edge of the marsh. ~Dense woods give way as you turn north along Powerline. Can you hear the absence of those clustered trees in the tones of the wind? The channel of grasses bisecting the forest have their own whispering inflections, their own quiet inhabitants. Perhaps your body moves differently here, and the packed earth resonates more subtly beneath your steps. ~The Wetland Boardwalk will not only clump underfoot, but will grasp and gulp at every step. The impossibility of stealth may obscure the songs of marsh birds – please step softly, or still your steps momentarily, to make way for their warbled virtuosity. ~Fern Oak, Meadow Run, and Old Field lead back to the park.Here are discrete spaces in which to shift between modes of listening. The sounds of humans may grow more present – and it is often easy to recoil from these after quietude in a sylvan soundscape. But please remain open to the utterances of this environment, as well. The sounds of play and melodies of speech, the insistent murmurings of swing chains and patient motor drones, and their combined, complex tapestry hint at a very different type of beauty, one of which you are very much a part. Although my creative process feels remade in the making of each work, I have long sketched my pieces visually and narratively before translating to notation. The growing shelves of sketchbooks in my studio often hold my favorite moment (or version) of a composition, one of potential and plurality, rather than the specificity of fixedness inherent in a completed notated work. Perhaps my affinity is because these fragments do not live in a single dimension, but conflate much of what motivates the work with the piece’s vocabulary in a blurred and messy amalgam – specific moments in time, unpolitic emotion, obsessive engagement with sound, treasured found text/objects, and all manner of language (unencumbered by social function) comingling with imagined gestures.

This summer I attempted to keep a work in this form – to give a version (more refined and abstracted) of this material to an ensemble. I am not sure what it is…the score seems part journal, part narrative, part graphic score. It is too large and fragile to be physically present for performances, so another layer of interpretation and abstraction is necessary: it is being presented in video format. The visual elements of the projected score are intended to create a shared framework of experience for performing musicians and the audience – a type of narrative environment. I do not work regularly with these improvising musicians [the Nodes Project] but I wanted a means of creating touchpoints of vivid, desired affect (narrative and visual structural elements) while still creating an open space for collaboration and improvisation. And for the emerging vocabulary to be communicative, I wanted the audience to be invited into that same shared space. The ‘piece’ lives somewhere between structured improvisation, visual art, and prose – or perhaps it lives in none of those places. But the process of making was physical and satisfying in a way that I had missed recently – letting myself spend all of my time in the potential and the tactile without the need to translate into fixed-ness. My gratitude to the Nodes Project (Andrew Rathbun, John Hébert, Keith Hall and Christopher Biggs), for giving me the opportunity and openness to explore these ideas. I’m sharing the full text and a panorama of the first half of the physical score here, in hopes of letting it live just a moment more in a slightly different dimension... a Child storm ill-fitted to the world supine, drinking in the shuddering light / nerves raw from seeking the rift of her moving knitting sluggishly each time she quiets it becomes almost arduous speak – in the cacophonous near-silence to encroach on that opaque whole-ness of it all with her artless ululation enticed and repulsed – in captive orbit Daughter steals the fragile leavings her assemblage, anesthetized, degrades at each caress its impermanence, momentarily, allowing her coalescence her deficiency mirrored immersed – story, language, song a Woman gnaws at simple bindings wielding phrases of borrowed armor perhaps she is less divergent in her abstraction, her cultivation perhaps she is simply less in the world the ripples of her awkward movements abated perhaps over years she neglects her discordance teeth set, lined eyes creasing mouth sutured against admission arrays and ciphers, translating her gray incongruencies into kaleidoscopes of color The composition students at Western Michigan University don’t write music like mine. And that seems like a good thing…for all involved. They have widely varying skills and aesthetics, each seeking a slightly different career in the arts. But music positions in industry and academia are increasingly competitive. And without sustainable careers, they most likely won’t make enough work or get enough feedback to ever realize their artistic potential. If I care about their success (and I probably should, since I moved my unsuspecting husband from Brooklyn to sunny southwest Michigan to teach these young artists), then I need to nurture their careers as well as their art, no matter how far removed from my own aesthetics and experiences.

There is growing interest in – and debate surrounding – entrepreneurship and arts education.[1] In Artivate - A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, Vikki Pollard and Emily Wilson simultaneously accept the importance of “developing curricula to address an employability agenda in higher education” and the pitfalls of applying generic business paradigms to careers in the arts.[2] There are some important concerns associated with teaching professional development in academic music programs: How does one simultaneously encourage thoughtful artistic growth and professional development? What kind of artists are we empowering to shape our discipline? How does one provide diverse groups of young artists with the beginnings of sustainable careers in the arts? These questions drove my development of a course called Entrepreneurship for Composers. Eleven students enrolled in the new class last fall – seven undergraduates and four master’s students. In EfC, we took the first steps toward building their careers; we built websites and wrote resumes, cover letters, and grant applications. We worked on public speaking skills through presentations of analysis projects. They organized off-campus concerts of their work (great experience that also looked good on their resumes). Each student also applied to ten external opportunities over the semester. These were discrete assignments with clear rubrics. And the students did well - almost everyone in the class had a new opportunity by the end of the semester. But here is what made it work for the actual students in the class – the individuals: I used a flexible approach. I didn’t tell them what kind of careers they should have or what kind of opportunities they should pursue. But they did need to express their goals – both short and long term – at the beginning of the semester. The remaining assignments would serve those ambitions. We started the semester with hard questions about their artistic identities and personal objectives (with an understanding that these would always be evolving). They had to describe their work, analyzing their artistic strengths and weaknesses. They started defining what kind of artists they aspired to be, and what they needed to do to realize those ideals. They were challenged to define their long-term goals, and then I helped them break those down into short-term ones. Everything from there on out was intended to help them reach those objectives. Some wanted gigs for the band they’d be focusing on after graduation, some wanted admission to a competitive graduate program, some focused on securing arranging or church gigs. They designed off-campus performances and their research topics. And they also found their own opportunities (though I gave them tools, resources, and ideas of where to start). I couldn’t have designed a fixed course that would have met their diverse set of needs. And unlike in many aspects of their education, in this class they weren’t sitting back passively waiting for someone to tell them how to become professional musicians. Instead, they were active and invested participants in their education. While every student described a slightly different set of goals, they each had to fulfill the requirements of the class. I didn’t care where the off-campus gig was, but they were still graded on adherence to their timeline for preparation, how smoothly the concert ran (including preparation of pieces and set/technical changes), rehearsals, and promotion (they had to get people in the door!). It didn’t matter if they wrote a cover letter for a job, graduate school, or a grant, but they were all graded on clarity, organization, the flow of ideas, and proofreading. I graded their websites on aesthetic consistency, audiovisual clips, editing, and a minimum number of working pages and links. All of these assignments were applicable to the professional world – students received much-needed feedback on writing and the letters they sent to potential opportunities and employers. And they were invested because these weren’t just assignments; they were shaping their public identities. We looked at the websites and music of young artists as well as established composers; the students made surprising and insightful observations, because it was all now applicable. They weren’t allowed to simply claim to “like” or “dislike” a website, someone’s writing, or a work of art; they had to employ critical thinking skills and communicate about aesthetics, form, and effectiveness. They assessed what they heard and saw, and then put those observations to work for their own goals. And in evaluating so many letters, websites, and performances, I learned as well. We discussed what we had done and where we needed to improve. Perhaps it goes without saying, but it is also important who teaches professional development and how institutions weights the topic. I made it clear from the beginning that the class was about building sustainable careers, not quick, easy tricks to jobs. The students know me as an active composer who teaches composition and theory, so they trusted me to prioritize the music above all else. And this wasn’t a weekend workshop taught by a business consultant; it was a university course taught by a full-time faculty member. The School of Music showed investment in the students’ futures by awarding credit (not even elective credit, EfC fulfilled a degree requirement) for an entire semester of professional development. For our discipline to flourish, we need a variety of active artists in each generation. These students can’t learn all they need by just writing or playing music and learning the theory/history sequence – they need to be taught how to participate in their communities, how to share their ideas and get their work performed, so they can continue to grow. And (thankfully) they can’t all be arts educators. I can’t teach them my path and they can’t follow it. So I’m willing to trust them to sort out their voices and what they need to be doing, as long as they keep asking themselves the hard questions along the way. [1] http://www.newmusicbox.org/articles/youre-an-artist-not-an-entrepreneur/ [2] http://www.artivate.org/?p=627 I have been a long time away from this blog. Not because I grew tired of adding my own ramblings to the noise of the internet, but because I was in a state of transition. I felt too ungrounded to articulate much beyond a sense of loss-ness. There was no reason to ask for a reader's time. But now I again feel compelled to attempt a dialogue with an unknown audience.

A week ago: I find myself alone on a cold beach in the early morning. A dense fog fills my ears and mouth and nose and everything is muted by heavy air. The thickness of it folds around me and coalesces in droplets on my skin. This is submersion. An angry ocean is smothered by the brume and the violence of its sound is nearly swallowed. I am swallowed. A feeling of euphoria builds in me, and behind it/beyond, a growing anxiety that I am utterly alone with this sensation. I'll never find the words to translate this moment. And never the sound, either. It seems so difficult to get an audience to experience this sensation of submersion. Even when surrounded by thick, rich sounds, those phenomena have an inception. Some catalyst that starts the compression of air into waves. The origin has a knowable and causal relationship with sound that localizes the latter--we hear music as coming from instruments and speakers, noise from machines. Sound is from, never at. We are not consumed by aural phenomena. Visual art installations are able to physically surround their audiences, they often become impermanent worlds. They can give one a sense of entering a space, something so difficult for sound (even through the waves of sound are always pressing against our bodies, invading our ears and the visual art is occupying discrete geographical space). The physics of the work don't matter, it is the sensation, the reception, that is important for either medium. How it resonates in/with the observing body. I want to consume the listener. How can I immerse one in thick, rich, expansive, unknowable sound? How to share this beauty? Perhaps I am still only conveying a sense of loss-ness... The safety of anonymity is nothing compared to the safety of abstraction. One would never stand up in a crowded restaurant and begin divulging secrets of past loves, private fears, and personal failures; but it is expected (encouraged?) in music. This is the safe, acceptable space for the unspoken aspects of self that are never to be acknowledged in the outside world. In my art, I confess, emote, wail, beg, and expose raw pain without restraint—I am safely hidden away behind the abstraction. My confidant/mentor/therapist/lover/priest: music. I relive traumas that could never be acknowledged publicly—without shame. I let my petty jealousies have voice and indulge in unrepentant emotional catharsis…and then I systematically present them to the world.

I asked a friend recently what would happen if we spent the entire day trying to communicate a single emotion to one another. Not speaking, not miming, but watching one another. Using face and body and voice abstractly. One could touch and respond to touch, but never point to something beyond the body. One could emote vocally, but never compromise the communication with defined language. One would have to watch the face more closely than ever—not watching for a chance to speak or rearticulate an idea just heard, but merely internalizing and being receptive. How awkward. How awkward, to not allow mitigating language or the concrete world lessen the vulnerability and trap the sensation in something finite. How terrifying, to spend a day giving oneself without hearing one’s ideas paraphrased, rearticulated, and validated by someone else. How freeing, not to justify one’s emotion with a pragmatic reference to experience....not to dilute content with explanation... A weekday morning on the downtown A train and everyone is quiet. A few of the people around me are reading or playing with one small electronic device or another, but most are just sitting there: glazed and silent. I get the sense that there should be sound here. That this many people in a space should mean communication, interaction, or at least some sonic artifacts of movement. But human sound is conspicuously lacking. The noise of the subway even seems subdued—still abrasive and mechanical, but lessened somehow, or far away. I am drowning in color and visual sensation; the florescent lights and the shuddering train make all the hues appear hyper-saturated, brilliant. I feel disoriented, like my senses are out of alignment. Somehow my ears are submerged in water and all is muted, but my eyes are overcoming the sense of loss with too much definition. I am aware of every leftover breakfast crumb on every tie; every detail of the grimaces of frustration, stress, or sleep deprivation around me; every frayed hem or stained shirt peaking out from beneath maladjusted over-clothes. The sensation is fantastic and devastating. It’s overwhelming. I panic for a moment, that I might be going deaf and therefore doomed to see this undiluted and stark world forever. The unforgiving sights keep assaulting me and I try to close my eyes, I try to focus on the sound that’s fading more and more and wrench myself away from the magnetic sight of apathy. But I can’t.

There is something amazing about malfunctioning senses. Something intoxicating about the dream-like sensation of being aurally or visually divorced from an experience one is otherwise completely aware of. Struggling to make one’s body receive the stimuli that must exist. When I was much younger and obsessed with the idea of synesthesia I tried to collaborate with a visual artist to build an environment of blue circles. The sound would be “blue” (or many octaves above the frequency of blue…) and moving in slow oscillations, the space would be a metal cylinder with elliptical cutouts letting blue light in, and the audience would be submerged in our lovely, insulated sensation chamber. But I wonder if that alignment is still what I’m looking for, or if a more exaggerated experience of the possible (and terrifying) disconnect of self from reality is needed to make me taste the art. There’s already so much lovely music out there, I think what I want is sensation... Perhaps it means more to have an experience that doesn't immediately make sense in the learned vocabulary of the world, because then it is more real. Yesterday, I caught myself closing my eyes and smiling at the sounds of a construction site—the irregular but driving rhythms, the low frequency rumbles of machinery, the glissed screams of chop saws. I was the only one standing there contentedly. People pushed past me while I subtly nodded to the rhythms. I felt that strange, giddy flutter deep in my ears as I listened to, and felt, the noise. It seemed profoundly beautiful and I felt absolutely alone. Hyper-idiomatic artistic language is always being lamented and debated. There is this seemingly accepted divide between the cerebral and the visceral, and perhaps a parallel divide between readings of what is consciously expressed and what is sincerely emoted. Noise doesn’t function within a layman’s “musical” vocabulary and seems to fall victim to the same criticisms of high art/abstraction/contrived language that haunts so much visual art. If one is especially invested in a sense (say, the way a composer is invested in the sense of hearing), that individual is often open to the profound experiences through that sense in every day life; they’ve trained their ears to be receptive. They often hear beauty in the mundane. The difficulty doesn’t seem to lie in capturing a moment of aural ecstasy, but in how to invite a listener into the language. I keep coming back to this desire to submerge my listeners in these aural experiences—to share with them a taste of profound beauty in noise—but the coded language has offered some stumbling blocks. We know what noise compositions are: they are loud, and aggressive, and uncomfortable (which is not a bad thing, I have some loud, aggressive, and uncomfortable compositional tendencies myself). They are arty and nerdy (again, not unlike myself). But then those preconceptions so quickly cheat us out of rich sensual experiences--in concert halls and out in "the world." And they often make one feel like a horrible dork for smiling contentedly at beautiful noise, whether in the concert hall or out in "the world"... A recent (and frustrated) sketch of "beautiful noise" |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed